|

|

TSI # |

85A-S748 (This is Treasure Salvors’ serial number for the bar. It was the 748th bar recovered. Bar number 748 is also its identification in the census prepared by Craig and Richards as an appendix to SPANISH TREASURE BARS From New World Shipwrecks, 2003.) |

|

Tag number |

0356 |

|

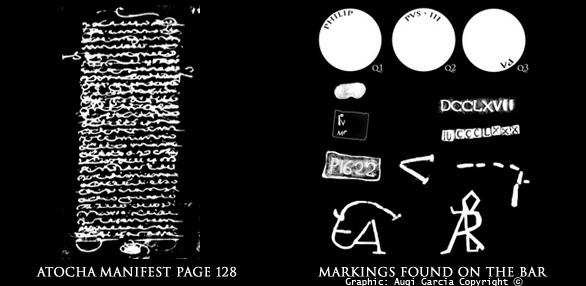

Atocha Manifest number |

767 (This number, stamped prominently into the bar, tells us that it’s the 767th bar made in Potosi in 1622.) |

|

Class Factor 1.00 |

(This is the highest possible rating for a bar, being the lower next grade 0.9, 0.8 , 0.7 and so on) |

|

Measurements |

35.5 by 13 by 10.5 cm |

|

Carat (Purity) |

2380 out of 2400 (99.16%) |

|

Weight in Troy Pounds |

88 pounds, 8.96 ounces |

|

Register and Page |

PB128 (This refers to page 128 of the original loading document prepared in Portobello, Panama, by the Atocha’s shipmaster de Vreder.) |

|

Manifest Comments |

L. de Arriola to SELF (Lorenzo de Arriola perished with the Atocha in 1622.) |

|

Date |

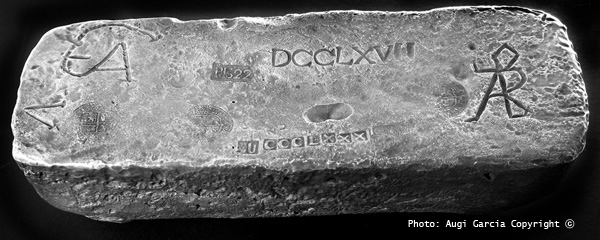

oP1622 (The letter prefix P with small o above it is believed to stand for the foundry of Potosí.) |

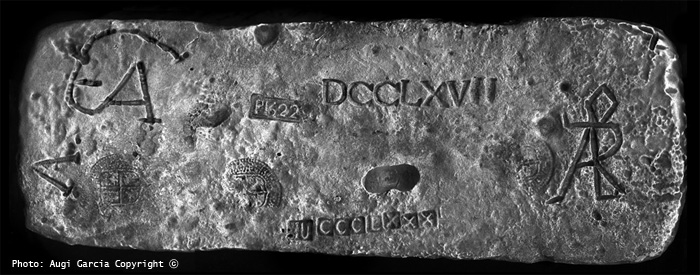

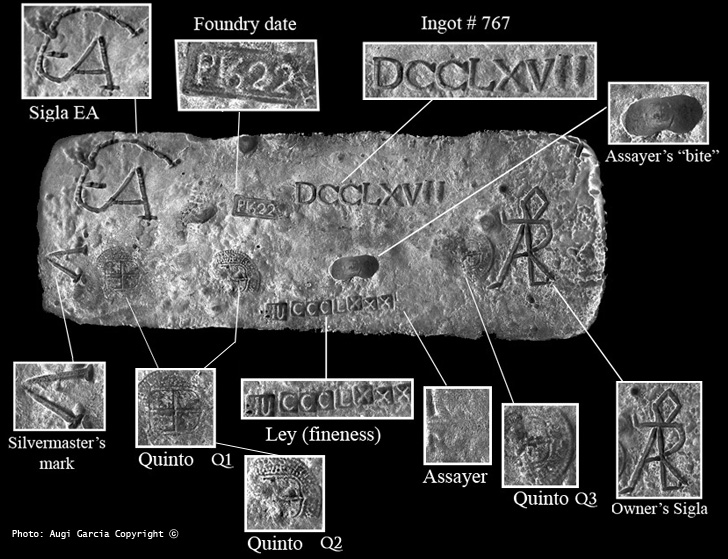

Comments on the markings:

1. Three tax stamps or quinto marks: The three quintos on this bar seem

to have been carefully aligned in a 90-degree-angle relationship that no one has

explained. All the dies used for the quintos have been and should be assigned to

Philip IV, Phillip III having died in 1621, but one of the quintos here shows an

ordinal III. This is not certain, but apparently an impression of the last “I”

was lost due to the way the die was impressed on the bar.

2.

“V” mark: V is the mark of Jacove de Vreder, the silvermaster for the Spanish

Silver Fleet of 1622. De Vreder was a Dutchman of Jewish origin, also known as

Jacob de Vreder. De Vreder died in the wreck of the Atocha. De Vreder had a

junior helper aboard the Santa Margarita, but he, de Vreder, was Master of the

all treasure in the Fleet, shouldering personal responsibility for logging all

treasure being transported. If a bar displayed his mark (V), it was properly

registered, not contraband. Bar 767 has de Vreder’s mark to the left.

3.

Assayer's bite: Here we see the so-called “double scoop” assayer’s bite. Once

the assayer tested the purity of the silver removed in the bite, the assayed

silver was kept as a fee for the process. The double scoop bite or “bocadillo”

is found only on bars made and assayed at the Potosí mint. Both the assayer and

an assistant had to work together, using a special tool, to scoop out the

peanut-shaped sample of silver.

4.

Date and foundry(?) mark: On the census prepared by Craig and Richards as an

appendix to SPANISH TREASURE BARS From New World Shipwrecks (2003) we counted

only 33 bars out of 901 that have the mark oP1622. That's only 3.6%. It is clear

that the date 1622 with the "oP" is very rare. While it is believed that the P

with the small o above stands for Potosí, it should be noted that monograms like

this usually stood for names that ended with the small, superposed letter, like

Pedro, so perhaps the attribution to Potosí is incorrect (P with small i above

would be more standard), and it may even stand for an individual rather than a

place.

5.

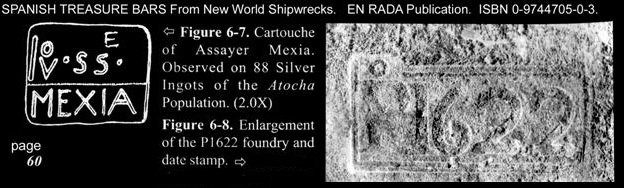

“M” mark: A small M stamped near the center of the bar tells us that the assayer

of the bar was MEXIA, who is also known from a few other Atocha bars bearing his

stamp. Dr Alan Craig in his book about Atocha bars describes this assayer mark

as rare.

6. Owner’s monogram (AR) for

Lorenzo de Arriola: Prominently displayed and deeply engraved on the right side

of the bar is the monogram of its owner, Lorenzo de Arriola. Arriola was a rich

merchant who had over 66 bars loaded at Portobello, Panama, for the Atocha’s

voyage to Spain. Sixty-six bars were approximately 6% of all the bars shipped on

the Atocha. It is surprising perhaps that Arriola put so much wealth in one

ship. Arriola personally accompanied the bars that he was shipping on the

Atocha, and he was among those confirmed dead in the sinking (according to

documents in the Archivo de Indias).

How Arriola managed to acquire the wealth that 66 silver bars represent, we are

not sure. He was involved in several businesses, but quite likely he had some

connection with the slave trade in Peru. He was registered in contemporary

documents as a vecino de Potosí. That means a “neighbor” or official resident

with all rights and privileges. He had lived for at least 10 years in the

Viceroyalty of Peru by 1622. The slave trade, supplying workers to the mints at

Potosí and elsewhere, was one of the most lucrative businesses in 17th-century

Peru. Few wealthy businessmen shunned its easy money.

7.

“EA” mark:In addition to Arriola’s monogram, the bar has a well-carved second

monogram composed of the letters E, A, and possibly L or I. This monogram is in

the upper left corner of the bar. We do not know who or what this mark

represents.

Lorenzo apparently obtained this bar directly from the mint at Potosí. From

there it was transported by llama to coastal Arica, then from Arica to Perico,

Panama, by ship, and then across the Isthmus to Portobello by mule, where it was

loaded on the Atocha. Somewhere along this route the bar acquired this second

“EA” monogram, but none of the marks registered on the Atocha manifest seem to

match this EA. From the way it is displayed it appears this mark stood for an

agent or trans-shipper of some sort, but the manifest says that the bar was

shipped by Arriola to himself, and we know that Arriola in fact died on the

Atocha accompanying his bars to Spain, so a trans-shipper was clearly not

needed.

represents.

Lorenzo apparently obtained this bar directly from the mint at Potosí. From

there it was transported by llama to coastal Arica, then from Arica to Perico,

Panama, by ship, and then across the Isthmus to Portobello by mule, where it was

loaded on the Atocha. Somewhere along this route the bar acquired this second

“EA” monogram, but none of the marks registered on the Atocha manifest seem to

match this EA. From the way it is displayed it appears this mark stood for an

agent or trans-shipper of some sort, but the manifest says that the bar was

shipped by Arriola to himself, and we know that Arriola in fact died on the

Atocha accompanying his bars to Spain, so a trans-shipper was clearly not

needed.

Another thought is that EA could be the mark of the ex-owner. This seems

implausible since when the bar arrived in Spain and was to be claimed, how would

it be verified who was the true owner of the bar if multiple owner and ex-owner

marks were on it? Rival claims could be made. The marks of ex-owners were

quickly effaced to forestall this confusion.

It has also been suggested that

perhaps EA was the payee of a bar Arriola was sending to Spain to pay a debt.

But there is no documentary confirmation of this transaction in particular, or

of this way of marking bars being transferred to another party.

Another

theory is that EA could be a variant form of the monogram of A. de Aguirre, cut

into the bar in this fashion to avoid marking the over the "quinto" tax mark.

But as can be seen on other Atocha bars, this was not a concern. Many Atocha

bars show marks that extend over the quinto tax stamps. Aguirre was a

businessman who shipped bars on the Atocha from Havana, but no connection with

Arriola is known. One final theory proposes that the bar was a tax payment for

slave transactions in Peru: The King was owed a tax on every such transaction.

The bar was being sent to the King in Spain to pay Arriola’s taxes. The bar

would have had at least two names on it: the man paying the tax (Arriola) and

the official who registered it as a tax payment. If the bar was a tax payment,

this would also explain why no averia payment was due or marked on the bar. The

averia was a royal tax on shipments going to Spain. It was marked as a diagonal

line on the bar, indicating what part of the bar was owed as an averia payment.

If it was a bar being sent to the King as a tax payment, it would be exempt from

the averia.

Another

theory is that EA could be a variant form of the monogram of A. de Aguirre, cut

into the bar in this fashion to avoid marking the over the "quinto" tax mark.

But as can be seen on other Atocha bars, this was not a concern. Many Atocha

bars show marks that extend over the quinto tax stamps. Aguirre was a

businessman who shipped bars on the Atocha from Havana, but no connection with

Arriola is known. One final theory proposes that the bar was a tax payment for

slave transactions in Peru: The King was owed a tax on every such transaction.

The bar was being sent to the King in Spain to pay Arriola’s taxes. The bar

would have had at least two names on it: the man paying the tax (Arriola) and

the official who registered it as a tax payment. If the bar was a tax payment,

this would also explain why no averia payment was due or marked on the bar. The

averia was a royal tax on shipments going to Spain. It was marked as a diagonal

line on the bar, indicating what part of the bar was owed as an averia payment.

If it was a bar being sent to the King as a tax payment, it would be exempt from

the averia.

The travels of the bar:

Every year the Armada del Mar del Sur (South Sea Fleet), composed of three or

four big galleons and a few small sailing ships, left Callao, the port of Lima,

on a 1,340-mile voyage to Panama.

The

galleons were heavily loaded with merchandise, much of it silver bullion and

coins, that had arrived at Lima only shortly before from the southern Peruvian

ports of Arequipa and Arica. Arica in particular was the preferred coastal

terminus of silver coming from Potosí, 120 miles to the southwest and 14,000

feet higher in elevation! Today both of these coastal cities lie in Chile.

The

galleons were heavily loaded with merchandise, much of it silver bullion and

coins, that had arrived at Lima only shortly before from the southern Peruvian

ports of Arequipa and Arica. Arica in particular was the preferred coastal

terminus of silver coming from Potosí, 120 miles to the southwest and 14,000

feet higher in elevation! Today both of these coastal cities lie in Chile.

The land journey of 63 miles between

Perico, the Pacific port of Panama, and Portobello, the Atlantic terminus, was

extremely dangerous. After two days on mule back, the convoy would arrive at Las

Cruces or Venta de Cruces. There it would be divided into two groups.

The first group would embark on the muddy, mosquito-infested waters of the

Chagres River. Sailing against the current in large, clumsy pirogues hollowed

from the trunks of giant trees, the boatmen would struggle upstream carrying

their 2-ton cargoes. Often part of the cargo was lost overboard or ruined by the

sun or the torrential rains.

Eventually, if luck was with them, they reached a shark-infested Caribbean

estuary defended by the great fortress, El Castillo de San Lorenzo. Sailing

under its protecting guns, the convoy then continued its journey along the coast

toward Portobello. Treasures and trade goods finally arrived at the King’s

Warehouse in Portobello Harbor, to be stored there until the Treasure Fleet left

for Spain.

The second group, carrying the most valuable cargo, especially the gold and silver, went overland. The steep and narrow trail sometimes disappeared altogether under the luxuriant tropical vegetation. Silver bars and sacks of silver coins were strapped on the back of mules, sure-footed animals trusted for the rough trip. Long mule trains were wrangled across the Isthmus by Negro slaves.

Travelers walked in Indian file, with

the team leader keeping a strict eye on the muleteers, who were always regarded

as potential bandits or traitors. There was additional danger from “maroons”,

fugitive blacks who lived in the forests and lurked near the towns. Maroons were

said to lie in waiting to carry off the womenfolk when they came to draw water

or wash their linen beside the river! They also served as informers and guides

for the English, who forever coveted Spanish gold and silver.

Despite its peril, this road served the Spanish well for more than three

centuries. Many treasure trains passed along it as they moved treasure from Peru

and the Pacific to the Atlantic and eventually Spain. The wealth of Spain

depended on keeping this little road open and secure. It became known to all as

El Camino Real—the "Royal Highway."

This was the perilous route of Lorenzo

de Arriola’s silver bar, which had traveled safely a very long way: from Potosí

overland to Arica, from Arica by ocean to Perico, from Perico overland by mule

to Portobello, and from Portobello by sea to Havana via Cartagena. Only the trip

from Havana to Spain remained.

Unfortunately, after so many months of traveling and such a great effort from

men and animals, this silver bar was not destined to complete the final leg of

its journey to Spain. A furious hurricane awaited the Atocha in the Florida

Straits. The ship and all its treasure went to the bottom. The bar settled into

the coral sands of the Florida Keys, untroubled by its new home amidst shifting

sands and currents, patiently waiting 363 years to resume its travels.

Bibliography:

- Allen, Paul C. PHILIP III AND THE PAX HISPANICA, 1598-1621: The Failure of

Grand Strategy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Craig, Alan K. and Richards, Ernest J. SPANISH TREASURES BARS FROM NEW WORLD

SHIPWRECKS. West Palm Beach: En Rada Publications, 2003.

- Grigore, Capt. Julius Jr. COINS & CURRENCY OF PANAMA Iola, Wisconsin: Krause

Publications,1972.

- Mathewson R. Duncan, III. TREASURE OF THE ATOCHA, Sixteen Dramatic Years in

Search of the Historic Wreck. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1986 (first American

edition).

- Sedwick, Daniel and Frank 1995. The Practical Book of Cobs. Orlando: Private printing. 4th edition 2007

Credits: Written and published by Augi Garcia all rights reserved. This article and its pictures can not be published without the written permission of the author. Many thanks to Daniel Sedwick (Final Edition and Research) , Duncan Mathewson (Research) , Philip Flemming (Edition), Dr. Alan Craig (Research) and Ernest Richards (Research), all of whom helped with editing or research.

-Reproduction of the articles in whole or part is strictly prohibited without written permission of the author/s.

![]()

![]()

Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC

P.O. BOX 1964 | Winter Park, Florida 32790

Phone: 407.975.3325 | Fax: 407.975.3327

We welcome your order, want lists, comments, material for sale or consignment and suggestions.

Please send email to: office@sedwickcoins.com